A few weeks ago, I was on a 10 day 70-mile / 110-km backpacking trip in the southern Rockies of New Mexico, here in the southwestern US. The Sangre de Christos mountains are gorgeous, a transition zone between alpine and arid ecosystems and Colorado Plateau and the Chihuahuan Desert extending north from Mexico. On foot, you can experience both environments within an hour or two of vigorous hiking.

It’s a place I visited as a teenager and was proud to come back to with my son and some other boys. Physically humbling. Spiritually moving.

One of the backcountry sites we visited is called Indian Writings, in a winding narrow valley that has had active human habitation for millennia. High and steep bluffs define a flat valley with deep soils along the winding North Ponil Creek. Waves of settlement — indigenous and invasive, peaceful and aggressive, hunter-gathers and farmers and extractors — have lived here and left layers and traces of scars and wonders.

Archeologists have worked here too, and we met two when we visited. They showed us several eras of occupation in successively close proximity: a subterranean refuge and dwelling well before the arrival of horses and the period when native peoples began building upwards, the remains of early pueblo stacked “apartment” structures, and the remote Spanish frontier homesteads of the early 16th and 17th centuries.

The lead archeologist and I had a great if brief conversation — he was surprised and excited to learn that I have worked on climate adaptation and resilience issues, much less since early 2000s. And I was thrilled that he was so active in considering how to use his expertise and discipline to expand our awareness of both problems and solutions. He is part of a group of archeologists who are eager to transfer their lessons and insights about how climate change has interacting with human lifeways.

Two points seem notable for this discussion.

First, insights about climate resilience come most strongly from scientific disciplines that encompass change over time, whether or they consider this “history.” Thus, ecology as a science should contribute a lot to climate resilience and adaptation, but in practice I find that most ecologists are actually quite “stationary” in climate terms and uncomfortable with the insight that ecosystems get periodically rewired and scrambled, such as in current period. This is really highlighted in the conflict between conservation and adaptation. However, paleoecologists are different — they have a lot of intelligence about the mystery of the interactions between shifts in critical climate variables and ecosystems (and often people too). The difference is that paleoecologists are interested in history, especially transitions. And their units of history are relevant to us today: they think about change over centuries and millennia, precisely the scope of change we are experiencing now and today.

Archeologists have a similar viewpoint. They pull back the lens far enough to see macro-level transitions, and even minor alterations in climate are deeply relevant. Anthropologists focused on contemporary cultures may lack this viewpoint. But I strongly agree that we can learn a lot of archeologists. They are effectively opening up our sample size of data from looking at, say, adaptation options in Fiji, Zambia, and Siberia today to dozens and hundreds of other relevant cases. We need that big sample set to learn — and to see what does and doesn’t seem useful.

Geology (and especially the geology of water — hydrology) also encompasses this viewpoint of transition, change, and history, though I sometimes wonder if the lens can pull back too far — looking more at scales of hundreds of thousands and millions of years, which is much harder for us to process as units of information.

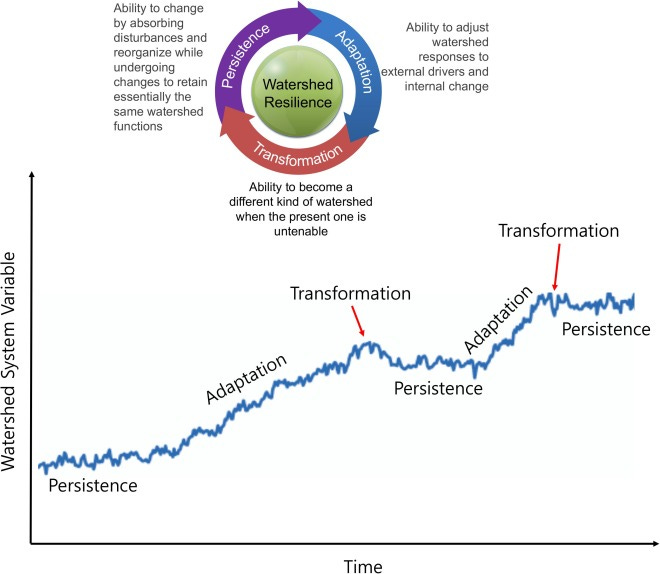

Second, this archeologist and I both have been deeply informed by so-called resilience theory, which is mostly closely associated with Buzz Holling, a Canadian ecologist who first developed a modern theory and interpretation of resilience — inclusive of but not limited to climate change — as early as the late 1960s and early 1970s. Groups like the Resilience Alliance and the Stockholm Resilience Center carry this work forward. Resilience theory has a theory of analyzing change over time that breaks resilience down into three modes or components: stability, slow and incremental change, and radical brief reorganizing change (persistence, adaptation, transformation). Resilience theory also has the insight that tipping points are important change markers, when a system begins to enter make a modal transition.

The archeologist was excited that I had integrated this work into my own. Indeed, with some colleagues we have a great paper on some new concepts and applications (and questions) in this space here and in the image below.

A lot of the “resilience community” is very insular and self-referential, and often feels both academic and isolated from decision making. They can feel irrelevant at worst. They often seem to be very enamored with their own neologisms. But perhaps the oddest thing about them is how little they understand water and the water cycle. In many books and articles from this movement, most or all of the examples are ultimately about water — impacts, shifts, drivers. Yet they seem to lack a theory for systemic hydrological or eco-hydrological or socio-eco-hydrological change. I would argue that the water cycle is — to quote Claudia Sadoff — both the medium for how humans will experience most of the negative impacts of climate change and — to quote myself — the medium through which most of resilience is articulated. Plain language and plain action seem to be necessary for each other at the moment.

In a way, the resilience community reminds me a bit of the Marxists in the late nineteenth and early twentieth century who argued endlessly about the gap between how Marxist theories described how revolutionary economic and social change should occur and how “practitioners” (community organizers?) actually worked to make those changes occur on the ground. The conflict between theory (ideology) and praxis (“practice”) can be gigantic. I am a scientist, but I am also a practitioner.

My comment to the archeologist in question was about this gap — and how his work showed that the evolution of human communities in this particular valley was an expression of the shifting nature of the water cycle and how humans have made use of available water there, including precipitation, surface flows, groundwater, the flood and flow regimes, and irrigation systems to manipulate and guide these watery expressions. An ecology changing radically at times, such as during the great drought at the end of the 13th century that triggered a major reorganization across the southwestern parts of North America and led to mass human population movements. There is no lasting resilience in this valley without water as a system. And not just in the valley, either!

I am hoping to carry these conversations and ideas forward, both with this archeologist, with archeology more broadly, and with you (!) here and in my own day job work.

John Matthews

Corvallis, Oregon, USA

This is incredibly interesting — thank you for sharing it!

It reminds me of a talk I heard as an undergrad almost a decade ago. Apologies to the academic who presented it — I can’t remember his name — but the ideas have stayed with me ever since.

I was just a baby climate thinker back then, but he spoke about adapting hydrological surfaces in the face of a turbulent climate future. His research explored how we might harness boom cycles — like mass flooding events — to help mitigate bust cycles of drought and water scarcity.

I’ve thought about that talk often as we’ve watched the water cycle grow increasingly unstable. Your piece is a helpful reminder that we’re not the first to wrestle with a challenging climate — and that perhaps there are valuable lessons in how others have done so before us.